Community Reviews

I am called Black, and for twelve long years, I have longed for my dearest Shekure.

I, Shekure, am not quite sure what I am doing in this story.

I am called Butterfly, and I was the one who drew the Death, and Mia thought I was the murderer.

I am called Stork, and I was the one who drew the Tree. Butterfly always envies me as I am more talented without the help from our master.

I am called Olive, and I was the one who rendered the Satan and drew the exquisite horse.

I am your beloved uncle, and I was preparing a book for our Refuge of the World, Our Glorious Sultan before being murdered by one of my apprentices.

It is I, Master Osman, and I wished to follow the path of Master Bihzad who blinded himself with a needle.

I am Esther, and my eyes were eternally at the windows and my ears were eternally to the ground.

I am a corpse, and I was Elegant Effendi before being murdered by a fellow painter.

I am Mia, and I read this book from page 1 to 508 whilst crawling and bleeding to death. So please would someone explain what the heck is this book about?

Jackie Chan: Who am I?

Sober version:

An interesting story regarding Istanbul in the 16th century. One day I'll visit the amazing Blue Mosque that a good friend of mine, Eddie, always talks about.

But seriously, though this book is amazing, I can't get into it. Totally not my rocknrolla thing.

***

One of the blue put this book on my desk. Got no idea which one though they pointed their fingers to each other lol.

Pamuk seems particularly adept at exploring mixed feelings, ambivalence, and multivalence. He delves into the ideals versus the perceived realities of love and marriage, the paradoxical effects of religious repression and competition with the West, and the contradictory ideas about representation in art. The apprentice system, which both nurtured great art and enabled rampant sexual abuse of boys by their teachers, also features prominently, along with the conflicted memories of those artists.

One notable flaw is that the discussions of Venetian versus Ottoman art appear to be based on inaccurate understandings of Western art history. Perhaps Pamuk intended to represent only how the Venetian tradition was perceived by Ottoman artists at the time, but it still comes across as a misrepresentation. For one thing, the influence between East and West was mutual, not a one-way street from West to East. Moreover, Venetian art, even in its rediscovery of portraiture and female nudes, was rich in religious, mythological, literary, and cultural iconography within the Western and Christian traditions. It was never simply an attempt to paint exactly what the artist saw, as the novel implies. Nevertheless, the points Pamuk makes about realistic individual portraiture, a "new" and controversial concept, are fascinating and seem valid, even the conflict that existed (in the Christian West as well) about whether this was or was not something God would approve of.

Regarding the characters, I found the women to be the most interesting and complex. Shekure, a beautiful, intelligent, and somewhat spoiled rich girl, must find a way to assert her power in a world where she is legally at the mercy of men. Esther, the Jewish trader and message carrier, enjoys a measure of freedom and autonomy but faces a difficult social position. I also wondered why Hayriye, the servant and concubine, was the only significant character who was never given her own time or voice.

This was my first Pamuk novel, and I'm not sure if I'm interested in trying another. I might be more inclined to explore his memoir of Istanbul.

In the airport, in the queue for boarding the plane, I saw Orhan Pamuk. I went up to him and told him about my admiration for him and that I had read all his books. I said I wanted to take a photo. He smiled and said, "I'll give you a test then." I nervously said okay. He asked, "In 'My Name Is Red', who was the murderer?" Although I had read it 15 years ago, for some reason I still remembered and gave the answer. He was a bit surprised and seemed pleased. There was a queue to board the plane and since we had some time, we had a chance to chat a bit. We talked about some of his books. He asked me questions about his latest book related to a strangeness in my mind, whether I liked it or not, etc. It was a very pleasant chat and finally he said that I was a good reader and so on. Of course, it was very nice to receive such praise from Orhan Pamuk. This is such a moment :)

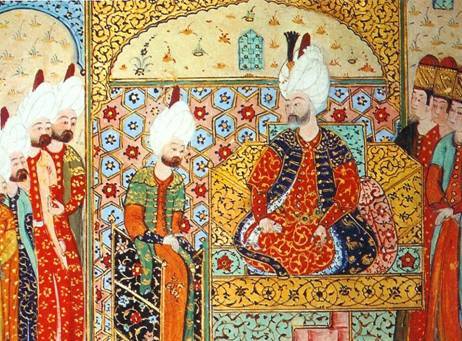

Orhan Pamuk's novel, which won him the Nobel Prize this year and has gained worldwide fame, translated into 24 languages, is a story set in the Ottoman era among illuminators. Through it, we are transported with Pamuk's skill, knowledge, and care to the world of Islamic art, its history, themes, colors, paintings, images, and famous tales like Khosrow and Shirin, Leila and Majnun, and Maqamat al-Hariri across the centuries.

I read this 605-page novel in two days, yet it took him ten years to write, research, and fill the manuscript with details. I'm still not sure what to say about it. On one hand, his strange narrative style intrigued me. He tells the story through many things and people, including criticism, the devil, a tree, and even the color red. Each chapter starts with "I am a tree" or "I am the killer" or "My name is red." It's truly a different, strange, and amazing way.

On the other hand, in the depth of my feelings, I felt deceived by his narrative. He made me a victim without my realizing it until his joke was left in my heart. I'm not sure if he intended to deceive the reader or not. But I can't find a better comparison than to say it's like the sharp, strange, "beautiful" needle described in the novel that takes away the light of the eyes in a way similar to "hypnosis." His way of writing is like what the Orientals saw in the East, where horror, oddity, conspiracies, and fleeting desires are the source of his charm and strangeness. But he doesn't mention this just for pleasure and entertainment like the Orientals did; he has his own philosophy.

The combination and unity that he insists on in every corner of his novel between the majesty of beauty, love, and the soul on one hand and ugliness, filth, oddity, and horror on the other hand greatly disturbs me. He shows them as if they are necessarily intertwined, as if this is the nature of things. He almost convinces you and beautifies them for you as if they are one thing. He mocks words like beauty, love, happiness, values, life, and death with a sarcastic and malicious care, comparing them with their opposites to make the reader despise them and desire them at the same time. He beautifies ugliness to make you desire it? Just like a skilled Chinese chef who knows how to make a delicious dish from what the soul rejects.

Therefore, I said that it's like that needle because it makes a person lose his view of the nature of things as they are after a while, and it blinds the eye gently and slowly, just like that needle. All of this is far from the talk about that absolute red as the source and end of all existence and life? And his hidden sarcasm towards the believers!!! Pamuk's philosophy tires me. It tires me in my struggle with myself to keep my view of ugliness as ugliness in his novel without being charmed by his magical words. His intelligence and cunning tire me. His disgusting sarcasm towards everything tires me. His devilishness tires me.

When I wanted to look at some of the paintings he mentioned to see how they look, and I searched for some of this art on the Internet, I discovered that from now on I won't be able to enjoy it without it dirtying my pages and disturbing my imagination of the "ugly" environment and circumstances in which they were painted. And thanks to Mr. Orhan... And to not be too unfair to Orhan, let me admit that these miniatures have always, and still do, send shivers and fear through my body, especially those with Chinese facial features, and I don't know why.

In any case, one should always be aware that this "beautiful needle that takes away the light of the eyes in a way similar to hypnosis" is in reality and far from the enchanting and magical expressions, a sharp and terrifying needle used to blind the eye in a horrible and simple way, so that a person loses his sight after it. Can you imagine how ugly this act is? And how much uglier is the talk about it? So what can be said about beautifying it and trying to polish it with malicious expressions that make the reader enjoy its ugliness if not to desire it? I can only think that it's uglier than ugliness itself.

And this is the novel. In short, my opinion of the novel is that it's different and devilish. It's tiring to the extent that I lost my cheerfulness when I finished it. They say Pamuk is talented. He is truly talented, but like a devil.

My death hides a terrifying conspiracy against our religion, traditions, and the way we view the world.

Black

The earthy scent of mud combines with memories.

Tree

I don't desire to be a tree; I long to be its meaning.

Black

It is crucial that a painting, through its beauty, calls us towards life's richness, compassion, respect for the colors of the realm God created, and towards reflection and faith.

Black

Painting is the silence of thought and the music of sight.

Stork

Painting is the act of seeking Allah's memories and seeing the world as He does.

Esther

Does love make one a fool, or do only fools fall in love?

Esther

Haste slows down the fruits of love.

Shekure

Just as those who know how to read a picture, one should know how to read a dream.

Red

Color is the touch of the eye, the music of the deaf, a word from the darkness.

Red

Wherever I am spread, I witness eyes shining, passions rising, eyebrows arching, and heartbeats accelerating. Behold how wonderful it is to live! Behold how wonderful it is to see. Behold - living is seeing. I am everywhere.

Red

Colors are not known but felt.

Uncle

What I called memory held an entire world - with time stretching infinitely in both directions before me.

Uncle

From now on, nothing was limited, and I had boundless time and space to experience all eras and all places.

Uncle

What is the meaning of all this, of this world? Mystery, I heard in my thoughts, or perhaps, mercy.

Enishte

Don't paint like yourself; paint as if you were someone else.

Master

He would force them to recall nonexistent memories, to envision and paint a future they would never want to live.

Black

For men like me, that is, melancholy men for whom love, agony, happiness, and misery are just excuses for maintaining eternal loneliness.

Murderer

Painting brings to life what the mind sees, like a feast for the eyes.

Murderer

It was Satan who first said "I"! It was Satan who adopted a style.

Satan

I believe in myself, and most of the time, I don't care about what has been said about me.

Satan

The opposite of what I say is not always true.

Satan

Was it not You who instilled pride in man by making the angels bow before him?

Satan

Men are worshiping themselves, placing themselves at the center of the world.

Shekure

I felt how my words were piercing his flesh like nails.

Black

They have emerged from Allah's memory. This is why time has stopped for them within that picture.

Woman

When you are a woman, you don't feel like the devil.

Woman

I wanted to be powerful and the object of pity.

Stork

An artist's skill depends on carefully attending to the beauty of the present moment.

Butterfly

The illuminator draws not what he sees but what Allah sees.

Black

He taught me that the hidden flaw of style is not something the artist chooses voluntarily but is determined by the artist's past and forgotten memories.

Olive

Time doesn't flow if you don't dream.

Murderer

I feel like the devil not because I've killed two men but because my portrait has been made in this way.

Shekure

Love, however, must be understood not through a woman's logic but through its illogic.

“Il mio nome è rosso” is a captivating novel by the Turkish Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk, published in 1998. Set in Istanbul in 1591, it weaves a complex and mysterious tale through the alternating voices of its protagonists. The story begins with the voice of a dead man, Raffinato Effendi, a talented miniaturist killed by a colleague. We are drawn into a whirlwind narrative that follows the tradition of storytellers, with stories within stories in a continuous framework.

The world of miniaturists under the Ottoman Empire is at its peak, with Sultan Murad III commissioning important works and exalting their art. However, a secret book being worked on by the most skilled miniaturists引发了越来越明显的亵渎指控. Three suspects, known by the nicknames given by their Maestro - Oliva, Cicogna, and Farfalla - are on one side, while Nero, who returns to Istanbul after twelve years, is on the other.

The voices of women and men, as well as unexpected protagonists like a dog, a tree, or a coin, tell this story. It is the designs that these men strive for, as they seek to reconcile art and religion. The color red dominates, symbolizing strength and will. Istanbul is the emblematic city of the encounter and conflict between the West and the East. Fanatical groups, then as now, see evil and filth in everything, even a cup of coffee.

The accusation is that of imitating European art, where the designs center on man and his vision of the world. The Muslim eye, on the other hand, can only be an instrument to show the only possible vision: that of Allah. This is why there can be no perspective in miniatures, and everything remains flat. The Muslim artist is also denied a personal style and the ability to sign their work, as it is considered an act of vanity. Thus, thoughts are divided between those who want to continue following the old masters and those who, inspired by the Europeans, want to find a way to reconcile different views on reality.

Fanaticism coexists with a more devious and material aspect: greed and ambition. What drove the hand of the assassin? Was it the thirst for revenge of one who craves success or the desire for justice of one who considers only the old precepts sacred? This is a story that combines the disputes that have truly animated the artistic environment with the age-old questions that have always tormented human beings, asking: “Who am I?”

“ Disegnano tutto quello che l'occhio vede, come l'occhio lo vede. Loro disegnano quello che vedono, noi invece disegniamo quello che guardiamo.”

“... non dimentichiamo che «artista» nel Corano è un attributo di Allah. Nessuno deve tentare di competere con lui. Che i pittori tentino di fare quello che fa Lui e affermino di essere dei creatori come Lui è il più grande dei peccati”

“ Il miniaturista ha un suo stile personale, un suo colore, una voce? Li deve avere?”