We find ourselves experiencing in words, on the inside of words, secret movements of our own. Like friendship, words sometimes swell, at the dreamer’s will, in the loop of a syllable. While in other words, everything is calm, tight. Words—I often imagine this—are little houses, each with its cellar and garret. To go upstairs in the word house is to withdraw, step by step; while to go down to the cellar is to dream, it is losing oneself in the distant corridors of an obscure etymology, looking for treasures that cannot be found in words.

We find ourselves experiencing in words, on the inside of words, secret movements of our own. Like friendship, words sometimes swell, at the dreamer’s will, in the loop of a syllable. While in other words, everything is calm, tight. Words—I often imagine this—are little houses, each with its cellar and garret. To go upstairs in the word house is to withdraw, step by step; while to go down to the cellar is to dream, it is losing oneself in the distant corridors of an obscure etymology, looking for treasures that cannot be found in words.

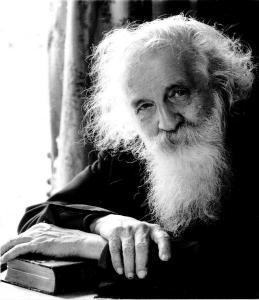

Here French architect and design theorist Gaston Bachelard elucidated something profound about architectural design. He did so by phenomenologically incorporating our lived experience rather than just focusing on the objective geometrical space. Bachelard transformed his architectural understanding into a poetic phenomena. He achieved this by mapping out the space hidden within our very lived experience. He firmly believed that no actual space could fully satisfy the poetic imagination. Instead, he motivated his readers to design as well as they possibly could to accommodate people, all while acknowledging that their task is never truly over. He also keenly observed that contemporary architects, in our modern era, tend to lean towards originalist thinking. That is, they have the idea of using classical forms, such as the pillar and arc, to derive further and more evolved abstractions for use as the building blocks for architectural sites. However, Bachelard accused this school of thought of eschewing lived experience in favor of abstraction. He pointed to examples of bleak, modernist “boxes” that alienate people from the beauty of aesthetic form and, consequently, from their own houses, distracting them with sophisticated symbolism.

He passionately argued that a house that is lived in is never an inert box. He rather wanted us to go back to the primordial understanding of space and shelters. If we were to question nowadays—What is a house? People would easily answer that it is somewhere we live for protection. But is it only that? If we were to press them for further exploration, it might seem like an idiotic act on our part.

But Bachelard wanted this very behavior of theirs regarding the house to be set aside for a moment. He wanted us to imagine, yes, imagine the beauty of its (house) form. Imagine how such an architectural design of a house could come into being? For him, every place, even the nook and crannies of our home, holds something intimate and has a poetic relationship with us. It is not all just an artificial thing. It has something human at its very core.

At the end, Bachelard thus motivates his readers, who are phenomenological thinkers and architectural designers, to reject the thoughtless forging ahead of classical forms for the sake of sophistication. Instead, he urges them to examine the lived space as a critically important artifact of, and instrument for, the future of human thought.